Posts Tagged ‘hannah waters’

Zombie Biology, Pt. 2: Zombie neuroscience

This is the second post in a 5-part series on the biology of zombies. More info and links to other posts here.

When I watched the first episode of The Walking Dead series, based on the comic book series of the same name, I was stunned: “They can show this on TV?!” Apparently we now live in a society where it’s ok to show a horse being disemboweled, with a mere warning of graphic imagery at the beginning of the episode. Some of my friends thought the plot dragged on through the first season a bit, but I loved it.

And one of the show’s most endearing details to me was that the safe haven city (supposedly) was Atlanta, Georgia. Not because I think it’s a great city or anything, but because this choice showed the emphasis the writers put on science: Atlanta was the city worth protecting because it is where the headquarters of the Center of Disease Control (CDC) are located. After all, if anyone is going to cure a zombie outbreak, you’ve gotta protect your scientists!

After surviving countless horrors, Rick and his small posse of survivors finally make it to the CDC, expecting to find a city of scientists working swiftly to find a cure for zombie-ism who would take them in. But when they go inside, they find a single man — the last man standing, working alone towards a cure in the vast complex.

Because no mad scientist is able to hold in his secrets, he quickly gives in and explains to them what he knows of the science behind the zombie outbreak. He asks his computer to call up TS-19: A video of the electrical impulses in the brain of Test Subject 19, a volunteer who allowed the scientists to study her as she succumbed to her zombie bite. As they watch the neuron’s of the still-human brain flicker on the screen before them, Dr. Jenner explains:

Somewhere in all that organic wiring, all those ripples of light, is you — the thing that makes you unique and human… Those are synapses, electric impulses in the brain that carry all the messages. They determine everything a person says, does, or thinks from the moment of birth to the moment of death.

The survivors gaze slack-jawed at the light show before them until the brightness begins to dim, with black roots growing up from the base of the neck into the brain, until everything goes black. “What is that?” they ask. Luckily, they have a SCIENTIST in the room!

It invades the brain like meningitis: the adrenal glands hemorrhage, the brain goes into shutdown, then the major organs — then death. Everything you ever were or ever will be, gone.

But wait, there’s more. After a little while, between 3 minutes and 8 hours, according to Dr. Jenner, the black roots turn to a glowing red, reactivating just the brain stem. (I’ll give the writers the benefit of the doubt and say the scientists recolored the zombie electricity later for effect.)

It basically gets them up and moving… [but] it’s nothing like before… Dark, lifeless, dead. The frontal lobes, the neocortex, the human part — that doesn’t come back. The you part.

While a nice shot, this explanation wasn’t satisfying enough for me. Sure, the brain stem might get em moving, but what makes a zombie want to eat other people? What makes them murderous, and angry?

I’m fortunate that I didn’t have to do this research because it would take far too many hours to get me competent in brain territory. But Dr. Steven Schlozman of Harvard Medical School made a fabulous video going through each aspect of zombie behavior and explaining what parts of the brain must be reactivated for a zombie to really exist! (via bioephemera)

But there is another zombie-related brain question — why do they want to eat human brains? BRAAAAAIIINS?

This never made sense to me. I mean, after a while, when the zombies gather in hordes and there are few living humans around, you would think they would need any energy they can get and not really discriminate by species or favored body part. Of course, not all zombies eat brains — in The Walking Dead they’ll eat anything, animals included, and the entire thing. (So resourceful.)

Perhaps brain-eating rose as a zombie characteristic because if they ate all of their victim, zombie-ism wouldn’t propagate very far. Gotta leave the prey a leg or two so that they can stumble and limp appropriately and, since zombies are altered in behavior, maybe they’re missing part of their brain. Got it.

Creepy zombie torso explains why she craves brains

Perhaps my favorite zombie movie is Return of the Living Dead, featuring punks fighting zombies (with a great soundtrack to boot). According to Wikipedia, this is also the film that debuted the zombies craving brains, with their stereotypical yell: “BRAAAIAIIINNNS!”

While hiding out in a funeral home, the humans manage to capture a decaying zombie torso — which I believe is given a tribute in the first episode of the Walking Dead (see how I did that? full circle!) — and they tie her up and ask her about her habits. “Why do you eat brains?” She told them that it helps her to cope with the pain of being dead. “I can feel myself rotting… [Brain] makes the pain go away.”

It’s unclear how exactly this helps — what is it about brains that would dull the pain of feeling your own body rot? But at least it’s an explanation, and, being as obnoxious as I am, for me any explanation in science fiction is better than none.

Zombie biology, Pt. 1: Richard Matheson’s bacterial symbiosis

This is the first post in a 5-part series on the biology of zombies. More info and links to other posts here.

A little girl zombie eats her victim in Night of the Living Dead

The rise of the zombie in pop culture is typically credited to George Romero’s ghouls from his Night of the Living Dead films, whose dead bodies reanimated with a taste for human flesh define our prototypical zombie. Romero doesn’t give a clear cause for their rise from the grave, with a vague mention in a television broadcast of a satellite returned to Earth from Venus emitting radiation. (Radiation could do anything back then!)

In a behind-the-scenes special about the making of the movie, Romero credits its creation to a short story he had written, “which I basically had ripped off from a Richard Matheson novel called I Am Legend” — a great horror story about Robert Neville, a man fighting for his life in Los Angeles against vampires. But the novel takes the vampire prototype and turns it on its head, with these creatures more recognizable as zombies to us than vampires. They aren’t the sneaky serial-killer types, but are rather stupid and gather in great hordes, and, like zombies, will feed upon one another if they must. (Yes, they have blood!) In an early chapter, Neville reads Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (as he sips whiskey and listens to Brahms while vampires scream outside his house), describing it as “a hodgepodge of superstitions and soap-opera clichés” compared to his situation at the time.

Most of the standard vampire tropes hold true: they’re sharp-toothed, blood-sucking, repelled by crosses and garlic, and can’t come out in the sunlight. But this is science fiction — there must be a scientific cause for these symptoms! While he’s skeptical of the scientists’ germ theory of vampirism that was proposed before the scientists became vampires themselves, Neville eventually overcomes his “reactionary stubbornness” and gets a microscope. (And Matheson doesn’t leave out the difficulties of microscopy or mounting samples, with Neville throwing his first scope across the room in frustration.)

When he finally gets his slide loaded with a sample of vampiric blood, he is shocked to see a bacterium in the sample — a bacillus, “a tiny rod of protoplasm that moved itself through the blood by means of tiny threads that projected from the cell envelope.” And from there much of the book turns to scientific inquiry with many moments that made me smile, like when Neville so urgently “needs to know!” that he nearly runs out of the house into a vampire horde. Oh, the drive of science! Or when he can’t make the pieces fit into his bacterial model and begins to work himself up into a fury:

He made himself sit down. Trembling and rigid, he sat there and blanked his mind until calm took over. Good Lord, he thought finally, what’s the matter with me? I get an idea, and when it doesn’t explain everything in the first minute, I panic. I must be going crazy.

But over the course of years, performing experiments on captured vampires and their blood samples, as well as doing a lot of hard thinking, Neville manages to explain to himself why the vampires act the way they do. Whether his explanations will be good enough for you is another question.

The bacterial lifecycle

Bacteria from the same genus as Neville -- this is Bacillus subtilis, while he found Bacillus vampiris

“I dub thee vampiris,” he says to himself when he sees the bacteria for the first time. The bacteria live in the bloodstream of their host and require fresh blood to live, living in a kind of symbiosis (described thus by Neville), with the bacteria generating energy for their hosts. But if there isn’t enough fresh blood around, a bacterium will sporulate, building a cell wall around itself to hide out until better conditions arise. When the host dies, these spores disperse, landing on a new host, with the new source of fresh blood reviving the vampiris bacterium.

In the novel, the bacteria were able to spread rapidly through the population due to dust storms, with the wind blowing the spores everywhere and the dust nicking peoples’ skin and thus creating a way into the body.

Neville’s discussion of bacteriophages is a moment of total scientific inaccuracy which I choose to ignore. His bacteriophages, which he describes as proteins that the bacteria secrete when conditions are poor, cause the bacteria to swell and explode, killing themselves along with the hosts’ cells. The thinking must have been that the bacteria need a way to kill their hosts so that their brethren spores can disperse — however a bacteriophage is not a protein, but rather a virus that infects bacteria.

Death by stake — an issue of bacterial metabolism

These vampiris bacteria can live with or without oxygen — aerobic or anaerobic metabolisms. In the bloodstream, they live without oxygen, but the second oxygen hits the system, they become parasitic, killing their host. And here’s where the stake comes in: The key to killing these vampires is creating a hole large enough to let oxygen into the bloodstream, causing the host to die immediately due a switch in bacterial metabolism. And when the host dies, the spores are released — and thus we have vampires exploding into dust. Once Neville realizes that it’s an issue of oxygen and not stakes or their material, he switches his method to simply slitting the wrists of the vampires to let oxygen in. “When I think of all the time I used to spend making stakes!” he says.

And why don’t bullets kill vampires? This is some embarrassing fabricated “science:” The bacteria cause the creation of a “powerful body glue” that seals bullet holes as soon as they are formed. (Though this body glue somehow can’t reseal the wrist slits.) The stake creates a large hole and blocks the body glue from resealing it, which is why they are such a potent weapon against vampires.

Other bacteria-based vampire symptoms

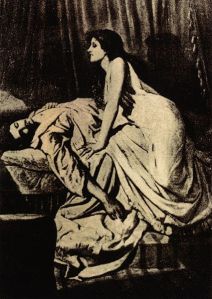

Philip Burne-Jones's painting The Vampire (turn of the 20th century)

Neville read that strong sunlight kills bacteria, which is why vampires can’t go out in sunlight. But without fresh blood, the bacteria can’t create energy — resulting in the coma-like state of the vampires during the day.

One of his first experiments is trying to work out the vampires’ aversion to garlic. After reading that garlic’s potent odor is caused by allyl sulfide, he goes to a chemistry lab and heats mustard oil and potassium sulphide at 100 degrees to create the compound. First he tried injecting it into a vampire — but nothing happened. He expected the bacteria to be killed by the allyl sulfide in a lab experiment, yet again nothing happened! He was so infuriated by this failure of his theory that he downed a bottle of whiskey, broke a bunch of glass, and shredded a mural he painted.

World’s gone to hell. No germs, no science. World’s fallen to the supernatural, it’s a supernatural world. Harper’s Bizarre and Saturday Evening Ghost and Ghoul Housekeeping. ‘Young Dr. Jekyll’ and ‘Dracula’s Other Wife’ and ‘Death Can Be Beautiful’. ‘Don’t be half- staked’ and Smith Brothers’ Coffin Drops.

He stayed drunk for two days and planned on staying drunk till the end of time or the world’s whisky supply, whichever came first.

Yup. Just a normal day in the lab.

He later realized that this chemical in the bloodstream wasn’t enough. It was the actual odor of the garlic that did harm — an allergen that sensitized and repelled the bacteria, and hence their hosts. Tells you something about in vitro and in vivo experiments, am I right?

“The germ also causes, I might add, the growth of the canine teeth,” he mentions once near the end of the novel. Good save, Matheson.

Vampire psychology

Neville wasn’t satisfied by this theory alone — what about the mirrors and crosses?

A new approach now. Before, he had stubbornly persisted in attributing all vampire phenomena to the germ. If certain of these phenomena did not fit in with the bacilli, he felt inclined to judge their cause as superstition. True, he’d vaguely considered psychological explanations, but he’d never really given much credence to such a possibility. Now, released at last from unyielding preconceptions, he did.

Before society collapsed entirely when vampirism was spreading, in terror people turned to religion to calm their fears — The vampires were cursed by god for their sins, and only by accepting god could you be saved! Neville theorized that when these people, now convinced that evil people were condemned to vampirism, were infected by the bacteria and found that they themselves were vampires, they were driven mad. The mere sight of the cross — a symbol of their rejection — made them want to flee due to their self-hatred.

But the cross doesn’t apply to everyone, he noted. He had one Jewish friend that, as a vampire, was not repelled by the cross. But the sight of the Torah made him run in fright!

Mirrors had a similar effect. Having to actually face the fact that they were vampires visually was enough to drive them nuts and induce them to flee.

Ending teaser (but not a spoiler!)

There are a few other awesome biological references in the novel — including the lymphatic system, medical applications and evolution, which I won’t go into detail about here so you can enjoy the read. But I will tease with this quote, especially appreciating that this book was written in 1954.

He looked into the eyepiece for a long time. Yes, he knew. And the admission of what he saw changed his entire world. How stupid and ineffective he felt for never having foreseen it! Especially after reading the phrase a hundred, a thousand times. But then he ’d never really appreciated it. Such a short phrase it was, but meaning so much.

Bacteria can mutate.

Bacterial vampirism: it’s awesome!

I’m no expert, but this was the only example of vampirism being caused by bacteria that I could find. This novel certainly inspired many later stories of plague-based apocalypse and biological transmission of zombie-ism, but, after a few decades of focusing on radioactivity and biological warfare, the genre switched straight to viruses (to be discussed later this week) and never went the bacterial track.

But there’s plenty of good reason to consider bacteria and other spore-based organisms when developing your zombie mythology, especially since there are a number of examples in nature (also to be discussed later). It’s an underexploited transmission mechanism! Get on it, filmmakers.

And one final note — I Am Legend is really awesome and you should read it. Trust me — there is MUCH to enjoy despite what you’ve read here. This is really a novel about human loneliness, perseverance, and our definition of normalcy, after all.

The danger of appealing stories: anecdata, expectations, and skepticism

This lovely image was taken by Russell Watkins in Sindh, Pakistan, and I was directed to it by a brief article in New Scientist. Reporter Seil Collins:

Covered in spiders’ webs, these cocooned trees in Sindh, Pakistan, are an unexpected result of floods that hit the region in 2010.

To escape from the rising waters, millions of spiders crawled up into trees. The scale of the flooding and the slow rate at which the waters receded, have left many trees completely enveloped in spiders’ webs.

Although slowly killing the trees, the phenomenon is seemingly helping the local population. People in Sindh have reported fewer mosquitos than they would have expected given the amount of stagnant water in the area. It is thought the mosquitoes are getting caught in the spiders’ webs, reducing their numbers and the associated risk of malaria.

I love this idea. My friends have been passing it around google reader, and it seems to make a lot of sense: More spiders, more webs, more dead mosquitoes in webs, fewer mosquitoes, less malaria. Bing bam boom.

The problem with it: It’s entirely based on anecdata. Anecdata has been my favorite word for about six months now, as well as a topic of fixation for me. It describes information from compiled from a number of agreeing anecdotes, stories, or items of hearsay — “psuedo-data [sic] produced from anecdotes” in the words of urban dictionary. Hearing that multiple people have made similar observations or had similar experiences can clue you into a trend, but hearing a lot of stories doesn’t prove anything. Storytelling is subjective and malleable, not the qualities of good data.

I haven’t been able to find a single scientific source for this mosquito/spider/flood story, though I’d give you a double high-five if you could find one for me.

So what’s the deal with data? We humans look around at our world, make observations, connect them, and use our rationality to draw reasonable conclusions. The story behind the photo makes sense: A number of separate correlations fit together. Who am I to say that we need SCIENTIFIC DATA, free from bias, to speak any kind of truth? After all, the chance to collect baseline data about mosquito and spider populations, average web coverage, mosquitoes per inch of web, etc. has passed and now we can only look back and try to remember what it was like before.

The problem with memory: It changes based on new information. And the problem with stories: They are borne from preconceived expectations.

I recently spoke with Timothy Mousseau, a biologist at the University of South Carolina, for The Scientist about the ecology of Chernobyl. If you scroll through media coverage of this topic, you’ll find many references to the Chernobyl site, which has received the highest level of radiation to date, as a wildlife preserve, one that has finally been able to thrive now that humans have left the area.

Mousseau, however, says this is a perfect example of anecdata. (Well, actually, I was the one who used the word. He thought it was very funny and I was the happiest.) Visitors go to Chernobyl expecting a wasteland, and instead they see the plants and animals that have returned in the past two decades. These people aren’t liars — they just can’t help but exaggerate. The visitors went in with expectations about what they were going to see, and when the reality was so drastically different, they went back home and told stories about the booming wildlife, even if it hadn’t actually returned to pre-radiation standards.

But many scientists, Mousseau included, have done a great deal of ecological research at Chernobyl and have found decreases in the number and diversity of many taxa, decreased sperm counts and brain size, and physical mutations, particularly in Mousseau’s specialty species, the barn swallow. (I’m going to write up more detail on this over the weekend, do not fear!)

This story of the thriving of wildlife in the absence of humans at Chernobyl, despite the nuclear fallout, is so appealing. It’s got the perfect ingredients: It’s a bit counterintuitive, but after a moment of thought, the pieces fit. “Ohhh, people were worse for the wildlife than radiation! Thank god this nuclear disaster happened and got rid of all the people so the animals can live in peace!” And as an added bonus, it lets us feel a little better about a terrible incident. It’s really no wonder the media clung to this story — but it’s probably not true. It’s just an instance of storytelling being interpreted as data, despite its contamination with human inference and expectation.

That’s what makes me nervous about this flood/spider/mosquito story. It has very similar appeal: The bit of surprise that a flood could decrease malaria, the “ohh” moment when the patterns seem to stack up, and, once again, a bit of good-feeling about a situation that was disastrous for many people.

Oh yeah, and that the reports are totally anecdotal, made by “people in Sindh.”

I want to believe it! It’s beautiful and makes me feel good inside! But the stories that are the most appealing are probably the stories that we should be most skeptical about. And they are also the most dangerous because they are the ones that will be retold over and over.

#nycscitweetup

There are many people in my life who think it’s strange that I like to meet up with my online friends in real life. “What if he/she is an axe murderer?” is a common remark. And it was very strange at first: The first time I met Bora I basically fled the scene because I couldn’t handle it. (Lucky for me, he stuck around for a second night so I had a chance to redeem myself.)

But it really is fun! I mean, we form these communities online of people that share very specific interests. Why wouldn’t you want to hang out with them?

I was lucky enough last weekend to get to spend an afternoon with Noam Ross (great ecology blogger, grad student, and awesome dude // @noamross) — and then last night a group of us got together at a bar in Manhattan and I had some great conversations with people I’ve known, as well as made new friends. (Awww.) I’ll shoot up a note next time we have one of these meetups in case any of y’all want to join in! We don’t bite… well, at least I don’t.

Anyway: I have the list of attendees and it is my duty to share. So here goes.

- Bora Zivkovic – the blogfather; scientific american blog network editor – @BoraZ // blog

- Angela Saini – author of Geek Nation: How Indian Science is Taking Over the World – @AngelaDSaini // blog

- Jennifer Gong – biology, archaeology, law, publishing – @jzgong // site

- Jeanne Garbarino – formidable science blogger and co-organizer of Science Online NYC – @themothergeek // blog

- Jon Stone – PR, newest client of @ccziv’s matchmaking service – @Asher8072

- Michael Habib – librarian, works for Elsevier/Scopus, ex-pat – @habib // site

- Ben Lillie – former physicist, current projects: story collider podcast, TED, my new BFF – @BenLillie // site

- Allie Wilkinson – science blogger, kayaker – @loveofscience // blog

- Krystal D’Costa – writes one of my favorite blogs, all around great person – @anthinpractice // blog

- Nancy Parmalee – hardworking science grad student – @nparmalee // site

- John Timmer – science writer for Ars Technica, co-organizer of Science Online NYC – @j_timmer // site

- Catharine Zivkovic – nurse, science comm, matchmaker – @ccziv

- Cassie Rodenberg – discovery planet green producer – @cassierodenberg // planet green

- Kirk Klocke – journalist/writer – @citizenkirk // site

- Lena Groeger – NYU science journalism student – @lenagroeger // site

- Douglas Main – NYU science journalism student – @douglas_main // NYU scienceline

- Stephanie Warren – NYU science journalism student – @steph_warren

- Rose Eveleth – NYU science journalism student – @roseveleth // site

- Holly Tucker – science historian, author of Blood Work – @history_geek // site

- Steve Mirsky — scientific american podcasts – @stevemirsky // site

If I forgot you, i.e. you missed Krystal forcing my list into your face/beer, leave a comment and I’ll update.

Here’s to next month’s #nycscitweetup! See ya there, I hope